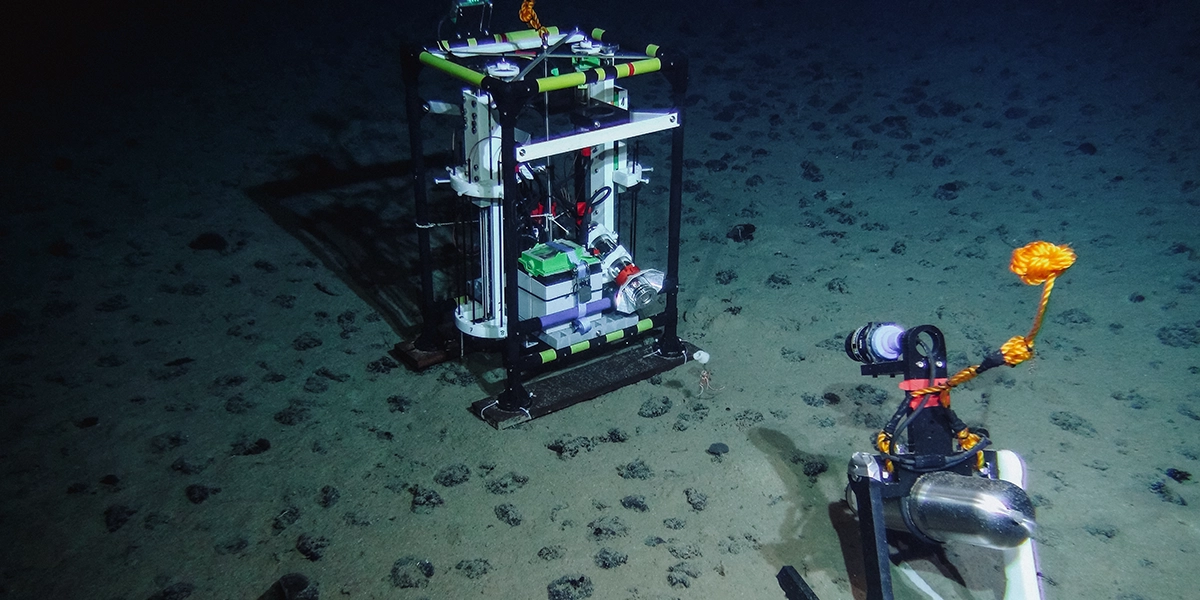

Did you know that we know more about the surface of the moon than about the deep sea? This shows how little we know about our planet’s largest habitat, the ocean, even though it plays a central role for life on Earth. It provides food, secures income, and regulates the climate. Yet this fragile yet vital ecosystem is increasingly under pressure: deep-sea mining is becoming more of a focus of global discussions. Since 2023, we have been a signatory of the moratorium on deep-sea mining and have reported on it. Much has happened since then – and yet the deep sea remains a place full of open questions and unresolved conflicts. In this update, we take a look at current political developments and shed light on why the debate about deep-sea mining no longer just concerns science and politics, but also all of us. For this, we asked Tim-Frederik Hahn to explain the latest developments and highlight what’s important now. Tim is conducting research and completing his doctorate at the University of Bremen on the European debate on deep-sea mining. Dear Tim, thank you very much for your willingness to give us a brief overview of the current debate!

How would you describe the current state of the political debate on deep-sea mining at the global and European level?

Fundamentally, a distinction must be made between national waters, which are the jurisdiction of individual countries, and international waters, for which the International Seabed Authority is responsible. At the global level, 32 states have spoken out against deep-sea mining. Of these 32 states, 14 are European states. Speaking out against deep-sea mining means that the states support either a moratorium, a “precautionary pause,” or, in the case of France, a ban on deep-sea mining. While mining companies are promoting mining and many non-governmental organizations are opposing it, the possibilities of deep-sea mining are being explored, but there is still no green light for commercial mining. The International Seabed Authority is in the process of developing a set of rules under which deep-sea mining might be possible, but has not yet completed this process. At the national level, only Norway has so far planned to permit deep-sea mining in its own waters in the near future. However, Norway also paused its plans last December. 2025 is an exciting year, as the International Seabed Authority (ISBA) aims to finalize its regulatory framework, and one of the leading deep-sea mining companies has announced that it intends to submit its first application for commercial deep-sea mining in 2025.

What specific role does Germany play in the European and international debate on deep-sea mining?

Germany is a leading player in deep-sea exploration and holds licenses from the International Seabed Authority for deep-sea exploration in international waters. However, in 2022, Germany called for a “precautionary pause” on deep-sea mining and will not support any applications for commercial extraction of raw materials in the deep sea until further notice. Germany is also committed to better protection of the deep sea and the precautionary principle at the international level. The precautionary principle means acting early and proactively to avoid environmental pollution.

ROV Team/GEOMAR (CC-BY 4.0) as well as the featured image

973 / 5.000

Are there currently products or technologies that contain materials from deep-sea mining? If so, how frequently do we as consumers come into contact with them?

Commercial deep-sea mining is not yet permitted, and therefore there are no products that use raw materials from the seabed. However, consumers frequently come into contact with the metals that could also be mined from the seabed in the future. They are used in smartphones and electric cars, for example.

How can individual citizens contribute to protecting the deep-sea ecosystem? Are there concrete options for action or initiatives that can be supported?

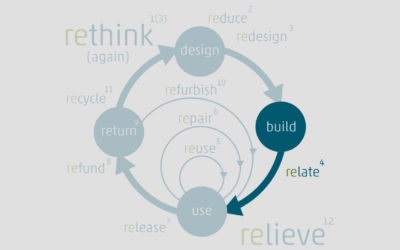

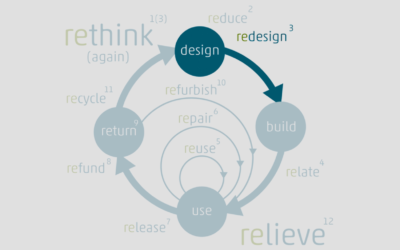

Individual citizens can contribute in their everyday lives, especially by engaging with the topic of deep-sea mining, supporting various NGOs, or generally supporting recycling and environmentally friendly business practices.

What was the biggest surprise or discovery for you personally in your research or during your research on deep-sea mining? Were there any unexpected twists or new perspectives?

When I began exploring the topic, I found two things particularly fascinating. First, how little we know about the deep sea and how much research discovers with each new dive in the deep sea. Secondly, I found it fascinating how many small and large companies have spoken out against deep-sea mining.

What makes you optimistic when you think about the future of the deep-sea ecosystem and the global efforts to regulate deep-sea mining? Are there any examples of progress or positive developments?

In my opinion, three developments in particular could benefit deep-sea ecosystems. First, the election of Brazilian oceanographer Leticia Carvalho as head of the International Seabed Authority. She succeeds Michael Lodge, who is considered more business-oriented and pro-deep-sea mining, and her election is associated with great hopes among environmentalists. Second, there is a strong commitment by NGOs and companies against deep-sea mining, which is constantly growing. And third, the conditions for mineral consumption are changing. Research into alternative technologies and increased recycling could lead to the minerals that are to be mined from the seabed perhaps no longer being needed in the future. Finally, a video tip: The Environmental Justice Foundation produced a piece that explores the topic of deep-sea mining from various perspectives and gives people around the world a voice. We also had the opportunity to share our perspective – a worthwhile portrait of the impacts and challenges of this important topic.